The mythical disease that shaped our sexuality.

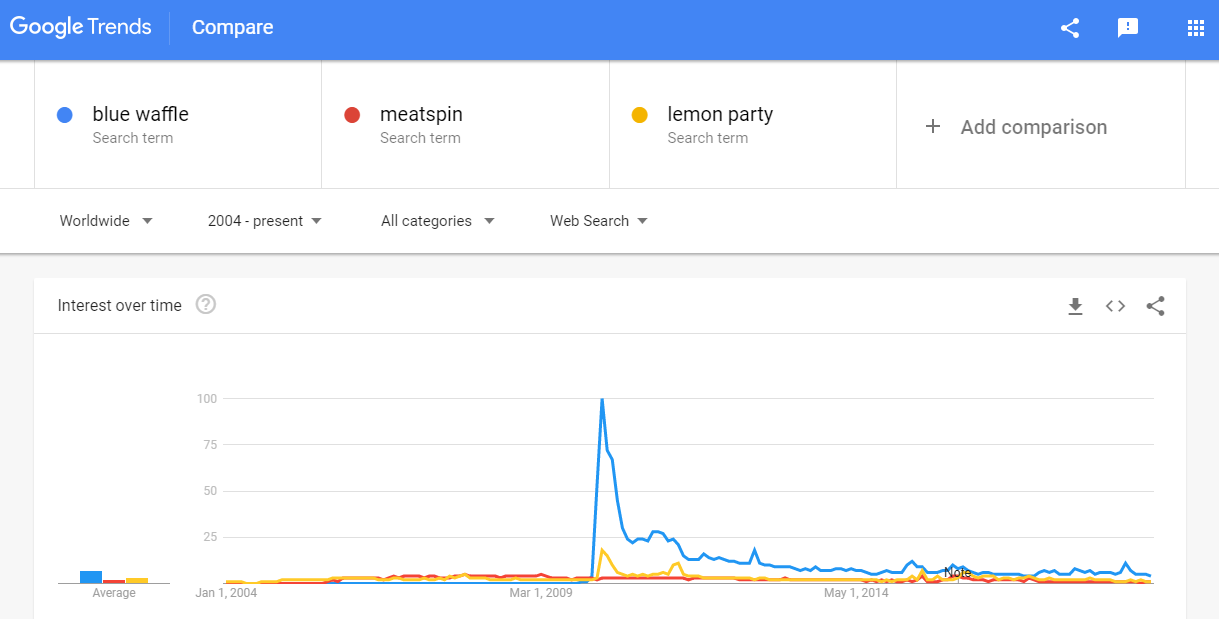

To understand how Blue Waffle became one of the most popular myths of contemporary adolescents, it is necessary to examine the culture in which it became prominent. The rise of Blue Waffle has been situated within a context of limited sexual knowledge and education, despite a persistent handwringing in media that teens are more sexually knowing than ever before. Studies of sex education classes, and the questions teenagers ask in them, demonstrate the severe lack of knowledge many young people have about their own bodies. For example, students were not always aware that genitalia do not all look the same (Bricker, 2015), or were unsure whether swallowing sperm would cause pregnancy (Sotiriadis, 2016).

Of course, a lack of knowledge is to be expected among adolescents; that?s why they are attending the sex education classes after all. But the information they are receiving in these classes at times fails to improve much upon their initial state of fearful ignorance. Educators are not always permitted to provide the necessary resources to dispel myths and fears and give the teenagers a rational understanding of sexuality, its risks and its rewards, and schools and teachers can often have an agenda of fear and deterrence rather than fact-based education. For example, in some schools the only anatomical photographs allowed in the classes are those of diseased and disfigured genitalia, as a warning against the dangers of unprotected sex, instead of a healthy understanding of natural bodily variations (Sotiriadis). While not every school employs this ethical minefield of an approach, it?s not that difficult to imagine similar tactics and adult biases leading to a combative, mistrustful atmosphere in the classroom, which has been shown to be deeply detrimental to learning. Teenagers may avoid asking more ?taboo? questions in their sex education classes, fearful of the responses from their teacher or fellow student (Sotiriadis).

So, unable to trust in adults to give them the full picture, teenagers turn to their friends, who are quick to spread their uninformed message of what is ?normal,? and what is ?disgusting? or scary. Peer pressure is one of the most persistently influential factors in adolescent sexual decision making (Sotiriadis). In an effort to bring meaning to the mysteries of sex, adolescents construct their own mythos of sexuality, sharply characterized by the sexual norms and vague understanding of condoms, STIs and the reproductive process they have received in their limited education. Like the ancient folk tales of why the sun rises and sets, in the absence of factual information teenagers resort to legendary accounts.

In the 1980s, common urban legends shared by teens had similar, though subtler, sexual themes ? the young couple canoodling on Lovers Lane who narrowly escaped the murderous ?Hookman? was a particularly popular example from this time (Brunvand, 1981). As television and print media became increasingly open in discussing AIDS and teen pregnancy, and access to porn and horror movies brought ever more graphic images into the cultural consciousness, the folklore circulated by teenagers likewise became more explicit while retaining a focus on the dangers of sexuality. For example, more recent popular myths of ?Hot Tub / Toilet Seat Pregnancies? are much more specific (though still incorrect) about sexual risks, claiming that women have become pregnant or contracted STIs without having sex through sitting on a toilet or in a pool or hot tub where a man has recently ejaculated. Sex, or even its approximation, could get you killed or pregnant is the moral, and the (almost always female) victim must suffer the consequences of her ?risky? behavior.

I?ve talked in more depth about the spread and function of urban legends (which is what Blue Waffle has now become) in a previous article. Creating a monstrous form in the absence of information, the Blue Waffle myth is functionally similar to the more recent Momo legend. ?Monsters are meaning machines,? Jack Halberstram (1995) has written. They rise up from the mayhem of possible meanings that people seek about things they don?t quite understand, filling the knowledge void with a vision too terrifying to be closely examined. In this way, the monstrous figure can be argued to actually have a protective function, guarding you from confronting the limits of your knowledge and understanding. The real horror is that which is remains unknown to you, ?the place where meaning collapses? or itself becomes monstrous (Halberstram; Kristeva, 1982).

The viewing of Blue Waffle is a surprisingly formalized, ?ritualized? process: as outlined earlier, the viewer is tricked by friends into looking at the image against their will, and once the image has been forced upon the viewer, they too proceed to spread it to unwitting others. Viewers are primed by the mischievous expressions of their friends to produce the socially acceptable reaction of shock and horror ? their reaction may even be filmed and shared to further condition people on exactly how this monstrous sexual deviation should be regarded. In the strength of their disgust, the viewer rejects and dissociates from Blue Waffle and by extension all non-normative forms of sexuality. They can take a personal comfort in their own relatively innocuous sexuality from confronting the abjectly horrifying ? I may not be completely sure I?m normal, but at least I?m not like that. As Halberstram writes, ?The monster, of course, marks the distance between the perverse and the supposedly disciplined sexuality of a reader.?

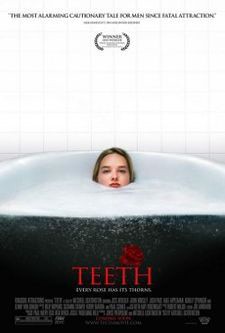

In modern fiction and film, monstrosity has tended to involve a ?horror of particular kinds of bodies,? Halberstram argues. Skin is ?the essential ? boundary of biological and psychic individuation? (Kristeva). Skin is the one thing we can look at to identify humanity, so archetypal monsters tend to gain their power to frighten from skin abnormalities, and the tension between human and non-human this can cause:

[Skin?s] color, its pallor, its shape mean everything within a semiotic of monstrosity. Skin might be too tight (Frankenstein?s creature), too dark (Hyde), too pale (Dracula), too superficial (Dorian Gray?s canvas), too loose (Leatherface), or too sexed (Buffalo Bill). ? Halberstram

Within this framework, conditions affecting the skin, such as leprosy (or puberty and STIs, in the case of Blue Waffle), are particularly dreaded because they threaten our ability to easily identify and categorize humanity within our societal codes. I obviously am not suggesting that skin disfigurement makes a person monstrous, rather that cultural fears are heightened when that tension is suggested, and pushed to the extreme when images are digitally altered as in the case of Blue Waffle. To view skin with a nonhuman blue pallor, skin that has been disfigured or violated beyond recognition, is to confront an absence of easy categorization ? ?the hide no longer conceals or contains, it offers itself up as text, as body, as monster.? (Halberstram)

Rituals play an important social role in encoding such unnamable phobias and taboos, and warding away the dangers of what we do not understand (Kristeva). Linda Williams (1984) has identified a similarly ritualized reaction in the viewing of horror films: ?Whenever the movie screen holds a particularly effective image of terror, little boys and grown men make it a point of honor to look, while little girls and grown women cover their eyes or hide behind the shoulders of their dates.? Rituals are usually gendered, concerned with separating the sexes and affording men more rights than women (Kristeva); Blue Waffle, with its focus on the taboos of the female body and female sexuality clearly adheres to this. Ritual allows us to process our unformed fears into something that we can safely interpret through our societal order: ?Through ritual, the demarcation lines between human and non-human are drawn up anew and presumably made all the stronger for that process.? (Barbara Creed, 1986).

However, the process of viewing Blue Waffle, and indeed other monstrous forms, is more complex than immediate, disgusted recoil. After all, horror is one of the most popular film genres, and Blue Waffle is a myth so pervasive it continues to spread digitally a decade after its creation. Despite our socially-sanctioned reactions of fear and loathing, something within us ? a ?latent perversity,? Halberstram terms it ? wants to continue looking at and spreading the images we loudly reject. As with our complicated relationship to horror, we are simultaneously drawn to and disgusted by the images, and this tension can provoke a cathartic, even pleasurable reaction, that keeps us coming back (Creed; Kristeva).

In addition, women can access a surprising power from the image, though on the surface it may seem to be another step in women?s sexual suppression. Julie Kristeva has written about how in a society of gender inequality, the male power ?apparently victorious, confesses through its very relentlessness against the other, the feminine, that it is threatened ? the feminine, becomes a radical evil.? Blue Waffle, in the very strength of its condemnation of female perversion, reveals the potential danger to male power of woman accessing this suppressed paradigm. Blue Waffle is easily comparable to older myths such as the vagina dentata, which reveal the vulnerability of male sexual dominance, and the fears men harbour about just how little separates women from seizing their authority. Linda Williams has written about the power of the female spectator in horror film..? When a woman looks at a monster in a horror movie, there is ?a recognition of their similar status as potent threats to a vulnerable male power.? In looking at, and encouraging friends to look at Blue Waffle, perhaps the female viewer is at least subconsciously recognising the potency of a sexuality that is entirely separate from the phallocentric worldview.

Building on this idea of ?when the woman looks,? I?ll conclude with an example of how Blue Waffle, encoded as it is with a bevy of other nameless fears, has actually become an effective starting point for a true, cathartic discussion of sexuality. Dr Anita Ravi (2017) has described the conversations she has been able to have with her patients by actively mentioning Blue Waffle in her clinical groups: ?The dynamic shifts because all of a sudden it?s like you?re speaking in code.? Putting a calm name to something previously unspeakable opened the door for vulnerable conversations about other frightening topics that it is a doctor?s responsibility to help their patient voice. Ravi has found other ?Blue Waffles,? or coded fears in medicine, aiding her work with sex trafficking victims for example by giving her the terminology needed to identify and understand what her patients are truly worried about (her presentation is fascinating ? you can watch it here).?It?s scary to think that there are things that people worry about that they may be afraid to ask ? and that we (doctors) don?t even know about it so we don?t think to ask,? she says.

In Ravi?s work, it is possible to see how the same logic could improve the poor sex education discussed earlier ? by having unbiased, fact-based conversations about the things teenagers are actually worried about, as a way of calming fears and building trust for deeper conversations. Blue Waffle has it all ? from fears about changing bodies and ?normal? sexuality, to worries about gender, equality, and the power dynamic of sexual relationships. In our strange compulsion to look at Blue Waffle?s photoshopped depictions, we can see the importance of using unaltered, educational images in sex education to show the healthy variation in human (and especially female) anatomy. In the violence and mutilation suggested by some of the Blue Waffle imagery, we can see the potential opening for discussing sexual violence more generally, conversations which are deeply needed by adolescents grasping alone to understand the rules of the sexual realm they are entering. Breaking through the conversational barriers guarded by monsters like Blue Waffle allows us to open the way for honest, trusting discussions and a de-mystified sexual future. Once you can give voice to a person?s deepest fears, meaningful communication becomes possible.